Bangalore District is located in the southeast of Karnataka State, in the centre of the South Deccan plateau, between the latitudes of 12° 39' North and 13° 18' North and the longitudinal meridian of 77° 22' East and 77°52' East. It has an area of about 2,191 square kilometres and an average elevation of about 910 metres (Bangalore rural and urban districts)

The Bangalore North taluk is more

or less a level plateau and lies between 839 to 962 meters above mean sea

level. In the middle of the taluk there is a prominent ridge running NNE-SSW.

The highest point (Doddabettahalli 962m) is on this ridge. The gentle slopes

and valleys on either side of this ridge hold better prospects of ground water

utilization. The low-lying area is marked by a series of tanks varying in size

from a small pond to those of considerable extent, but all very shallow.

Bangalore South Taluk represents

an uneven landscape with intermingling of hills and valleys with bare rocky

outcrops of granites & gneisses raising 30-70 meters above ground level are

common in the southern portion. The highest point is 908m above mean sea level

and the lowest at 720 meters above the mean sea level. Southern and Western

portions present a rugged topography composed of Granitic and Gneissic masses.

The eastern portions of the Taluk form an almost featureless plain with minor

undulations.

Contour lines are used to represent elevation. An elevation is represented by a contour line when it is drawn on a map. The elevation of each point on the map that touches the line should be the same. You can tell the height of a line on some maps by the numbers on the lines. Different altitudes will be represented by contour lines placed adjacent to one another. The slope of the terrain increases with the proximity of the contour lines to one another.

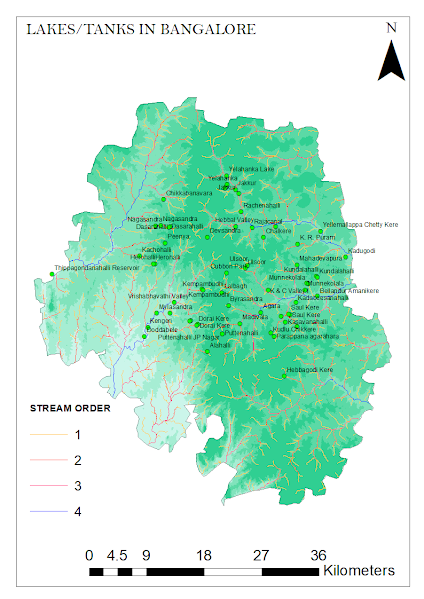

Bangalore City's naturally undulating landscape, which includes hills and valleys, is ideal for the creation of tanks that catch rainfall, store it for later use, and guarantee ground water replenishment. Thus, tanks are dynamic ecological systems that are essential for the survival of all species, including humans. When a lake in Bangalore overflowed, the extra water would flow into the next lake in the cascade because tanks in Bangalore were constructed in a cascade from higher to lower elevations. Along the land's natural gradient, water flows both north to south-east and north to south-west. There is a central ridge in the center of the region with maximum elevation 943, Minimum elevation 600 and average elevation in Bangalore city is 910 as per shown in Fig. 3.

By holding vast volumes of water and releasing it when there is a shortage, a lake functioning properly can lessen the effects of floods and droughts. Additionally, tanks recharge groundwater and improve the water quality of downstream watercourses. Tanks often raise the lowest temperature year-round while lowering the maximum temperature. Bangalore has cooler climate because its elevation is more than 900 m above sea level. The more you go upward from earth’s surface, the average yearly temperature of a place decreases. That is the only reason. Any place of similar elevation (and located in a similar latitude) will be as cool as Bangalore.

TANK SYSTEM OF BANGALORE CITY

In a city like Bengaluru, which lacks a perpetual river and is dependent on several tanks for both water supply and leisure, tanks are particularly crucial. On the city's uneven landscape, several tanks have been built over many years. Its geography makes it easier to use the tanks since it made it possible to create a chain of tanks that feed into one another and provide enough water. Tanks are beneficial for recharging groundwater as well.

Kormangala-Challaghatta Bangalore, which is situated on a ridge, has three valleys that serve as watersheds: the Koramangala Challaghatta Valley (K&C Valley), the Hebbal Valley (H Valley), and the Vrishabhavati Valley (V Valley). K&C valley, which spans an area of 255 square kilometres inside the boundaries of Bruhat Bengaluru, is the biggest, followed by Hebbal valley (207 square kilometres), and Vrishabhavati valley (165 square kilometres). While Vrishabhavati Valley enters the Arkavathi River, a tributary of the Cauvery River, both K&C Valley and Hebbal Valley unite at Nagondanahalli Village and run on to the Dakshina Pinakini River.

WATER STREAM

CONNECTING LAKES/TANKS

The above study provides a possibility to work further on several Bangalore lake series depending on their stream order.

No comments:

Post a Comment